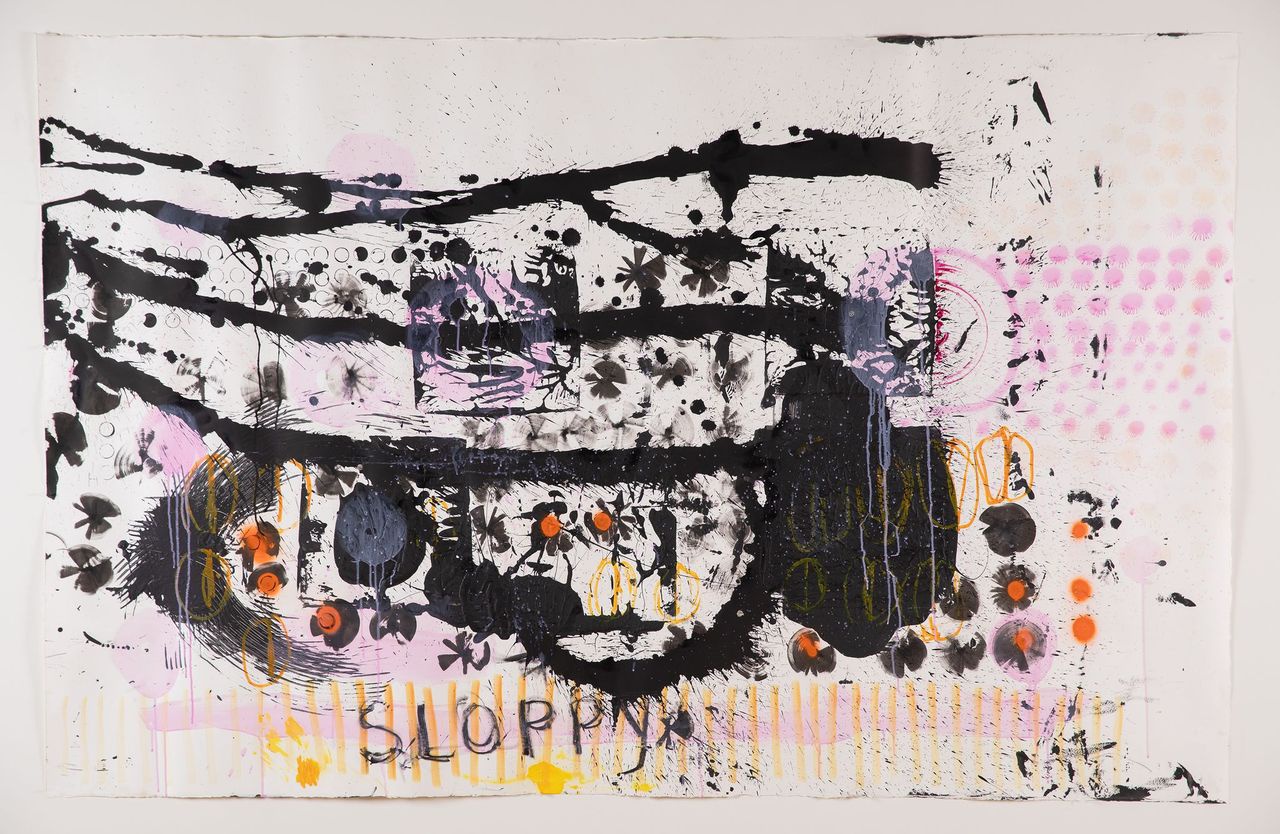

George Long, “Namesake,” 2024.

Square One, George Long’s solo exhibition at Marcia Wood Gallery through June 22, comprises large, unframed works on paper and a series of figurative clay sculptures on five low, black pedestals in the center of the gallery. The physical presence of the artist’s hand and the obsessive quality of his artmaking is palpable in all these works. The title of the show refers to the squares — both sculptural and drawn — that have preoccupied this artist since his earliest forays into exhibiting his work.

However, this exhibition is much more than a quip on returning to his sources. The titles of Long’s works are unrevealing, and their meanings seem too simple, but this is part of this artist’s sensibility. Long is a serious joker; his flippant facade covers the intensity of his artwork lest you, the viewer, get too close.

Long’s diptych, There Was That Other Thing (2024), is startlingly beautiful. Scribed on top of a complex, dark underprinting of block-printed squares are circular scribbles in a luscious Pepto Bismol pink. Together, they recall the black and pink of Good & Plenty candy. The two panels have uneven edges and shapes that call attention to the space between them. The straight, clean edge that divides the two panels reveals about an inch of the wall behind them.

This contrast is visually seductive — the drawing is so direct in its making that one almost feels like it was discovered, not made, like the cave paintings on the walls of Lascaux. This primal touch has the strong aura of authenticity; the work is made because the artist must make it. There is no other agenda.

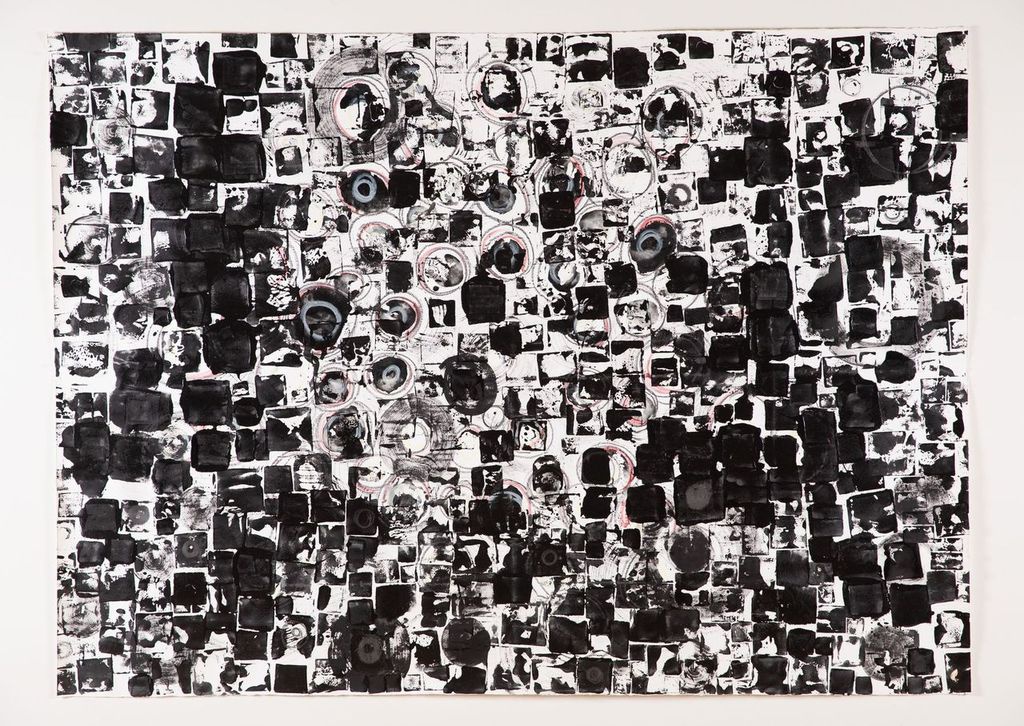

The pleasingly uneven quality of the artist’s stamping makes It’s Really You (2024) pulse. Each square has been printed on the paper with a slightly different touch, but one feels the frenzied quality of putting each part into the whole, creating a crescendo of movement and lightness. There is something quite old-fashioned in this drawing in terms of structure and composition, but the different passages made with the artist’s stamp (a block) at varying pressures within the same work create a lopsided grid that suggests the artist’s experience of the urban landscape.

The five pedestals lined up in the center of the gallery support figurative clay sculptures in which touch and form come together triumphantly. Four of these pedestals have sculptures that are composed of two or three human feet that end at the joint of the ankle or shin. The physical touch in the modeling of the clay is palpable; the artist’s hand is so present that the traces of his process lend the work an emotional presence akin to Rodin. What Does Longing Teach (2024) has the feet at angles that express two humans coming together in intimacy. Each aspect of this work — from the way the two limbs touch to the patina of colors rubbed into the clay — feels natural, as if the work’s coming into existence had been an unpremeditated act.

There is a crudeness to the work. Nothing in this exhibition is refined. It is a series of primal moments that look as if the artist has put his entire self into them; all pretense is gone. Long seems to be literally laying his emotions bare in this work.

What Is Missing (2024) displays another type of intimacy with three feet that nestle into one another. The way these three body parts fit together is a balancing act of form; these small parts exude the presence of full bodies. The generative force of this work is its physicality, which has an emotional presence without heavy handedness.

Long’s use of repetition in his drawings made by using blocks and squares as printing tools resurfaces in Getting Old and Looking Up (2024), a group of 96 ceramic heads, each with a totally different facial expression. These small, sculptured heads (which are each about an inch-and-a-half in diameter) lie in a pile on the pedestal; it is interesting to see how each is different from the others and to ponder what the artist might be communicating in each face. Though viewers may find themselves looking at each head, ultimately the “more is more” principle unfurled in this work gives it its power.

Square One reveals George Long as his authentic self. He has gotten out of his own way, gone beyond his sheer talent and allowed the viewer to see the process of making, of becoming and feeling in his subjects with rawness and lack of pretension. His repetitions and ruminations span a bridge between his two chosen mediums. It is at this moment that the audience must allow themselves to see and experience what is at play.

::

Deanna Sirlin is an artist and writer. She is known internationally for large-scale installations that have covered the sides of buildings from Atlanta to Venice, Italy. Her book, She’s Got What It Takes: American Women Artists in Dialogue (2013), is a critical yet intimate look at the lives and work of nine noted American women artists who have been personally important to Sirlin, based on conversations with each one.