In 1512, four years after the chapel’s inception, Michelangelo climbed down the scaffolding for the final time after painting God Separates Light from Darkness. Strangely, it turned out, the Master had put off the first day of creation for the very end. Legend has it that he (and his crew) knocked it out in a marathon eight-hour session. Given the drying time of fresco this is entirely

possible; at any rate, the result was one of Michelangelo’s most spontaneously painted compositions. Frame any detail from the vast background behind God’s parting thrust and the panel reveals its abstract construction. If we imagine its execution in real time, Michelangelo would’ve spent some hours conjuring the concentric bands and nebulous forms that surround God’s massive contrapuntal figure. It’s not surprising that contemporary artists like Sagerman would find inspiration in its abstract potential.

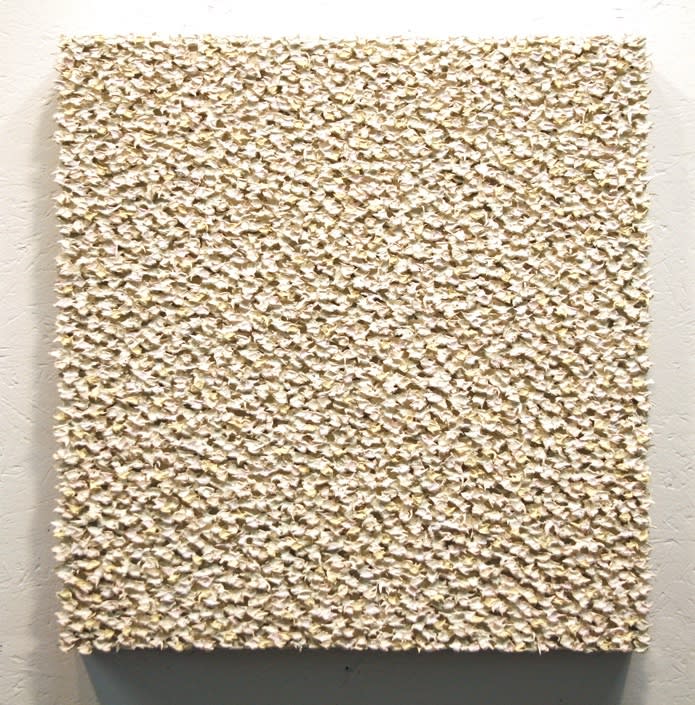

Sagerman pays homage to Michelangelo’s forms during the preliminary sketch phase of each painting. His past compositions have largely relied on straightforward gradation changes requiring no drawn plan. Thus, Cumulus marks an interesting shift, as he allows himself a structural field to build on. Until now, the artist employed a multi-colored — even fluorescent — palette, all the while experimenting with different ways of raising the brushstroke off of the canvas. For Cumulus, he settled on one color per piece, and one pattern of stroke, giving each painting a distinct identity based on both color and vortex-like swirls.

The titles refer to the brushstrokes, and the number needed to complete the surface, e.g. 17, 172; 15, 942 and so forth. There is obviously a deeply meditative component to his studio time, and the artist – who has a Ph.D. in Hebrew and Judaic Studies – also writes of a long interest in Buddhism. But here’s an irony: at a reasonable pace of 360 stroke placements an hour, each work would require around 50 hours to finish – the time it would have taken Michelangelo to paint God Separates Light from Darkness six times.

For the viewer, the result of these many hours is a luminous exhibition that is best experienced in the gallery, where Sagerman’s super-saturated colors and deeply scalloped strokes move the eye kinetically (and hypnotically) across the canvases via shapes whose contours could only be traced to their 16th century origins by a Renaissance savant.